KASSÉ MADY DIABATÉ

For almost half a century Kassé Mady Diabaté has been recognized as one of West Africa’s finest singers. He is a descendant of the most distinguished griot family of the ancient Manding Empire, the Diabatés of Kéla, and his name, alongside other griot legends Toumani Diabaté and Bassékou Kouyaté, is equivalent to musical royalty in Mali. The Manding Empire was founded in the 13th Century by the emperor Sunjata. It swept from one end of West Africa to the other, from Casamance on the Atlantic coast all the way to Burkina Faso, thousands of miles to the east. Sunjata used a hitherto unheard of weapon to bind all his disparate peoples together: music.

Music became a formidable political tool and turned the hereditary Manding musicians or djelis (griots) into a powerful caste. Today, having survived centuries of change and turmoil, that caste is still flourishing. Drawing on themes as old as the empire itself and melodies learned in childhood, the modern griots still mediate for social order. It explains how an artist such as Kassé Mady Diabate can rise to such a degree of excellence and become a national treasure in Mali.

Kassé Mady was born in 1949 in the village Kéla. His aunt was the great griotte Siramori Diabaté, while his grandfather was known as ‘Jeli Fama’, which means ‘The Great Griot’, thanks to the gripping quality of his voice. When Kassé Mady was 7 years old (a significant age in Manding culture), the elders of the family, including Siramori, realized that he had inherited his grandfather’s vocal genius. They schooled him and encouraged him, until he was able to launch his own career. He would go on to play a role in the most innovative moments in Malian music over the next five decades, first in his own country and later with landmark international collaborations.

In 1970 he became lead singer of the Orchestre Régional Super Mandé de Kangaba. With Kassé Mady’s remarkable singing the group won the nationwide Biennale music competition in the Malian capital Bamako. The festival had been set up by the government, as part of a Cultural Authenticity initiative across all of the newly independent West African states, encouraging musicians to return to their own cultural heritage. At the BiennaleKassé Mady caught the attention of Las Maravillas de Mali, a group of musicians who had studied music in Cuba, and returned to Mali to perform their interpretations of Cuban classics. The Government was putting pressure on the group to incorporate a more Malian repertoire and so they invited Kassé Mady to join them as lead singer. With their young vocalist at the helm, the Maravillas, later known as Badema National, achieved huge success throughout West Africa, with songs sung in a Cuban style, but with a new Manding touch.

In 1988 Kassé Mady left Mali and the Badema National behind and moved to Paris, where he recorded his first solo album for the Senegalese record producer Ibrahima Sylla. He spent the next ten years in Paris, recording Fode, then Kéla Tradition, an acoustic album of Kéla jeli songs. Moving back to Mali in the late 1990s, several collaborations followed, many of which have become landmark recordings: Songhai 2, the album he made with the flamenco group Ketama and Toumani Diabaté, and Koulandjan, on which he collaborated with Taj Mahal andToumani Diabaté, an album which was famously cited by Barack Obama as one of his favorite albums of all time. Collaborations with Toumani continued and he starred in the Symmetric Orchestra and Afrocubism projects, both recorded by World Circuit.

Solo projects during the past decade have included the acoustic album Kassi Kassé, produced in 2002 by Lucy Duran, and Manden Djeli Kan, released on Universal France in 2009 and garnering 4 and 5 star reviews: ‘the star is always the brilliant vocalist’, said The Times reviewer, while the 5 star review in the Financial Times said simply ‘Time stops still’.

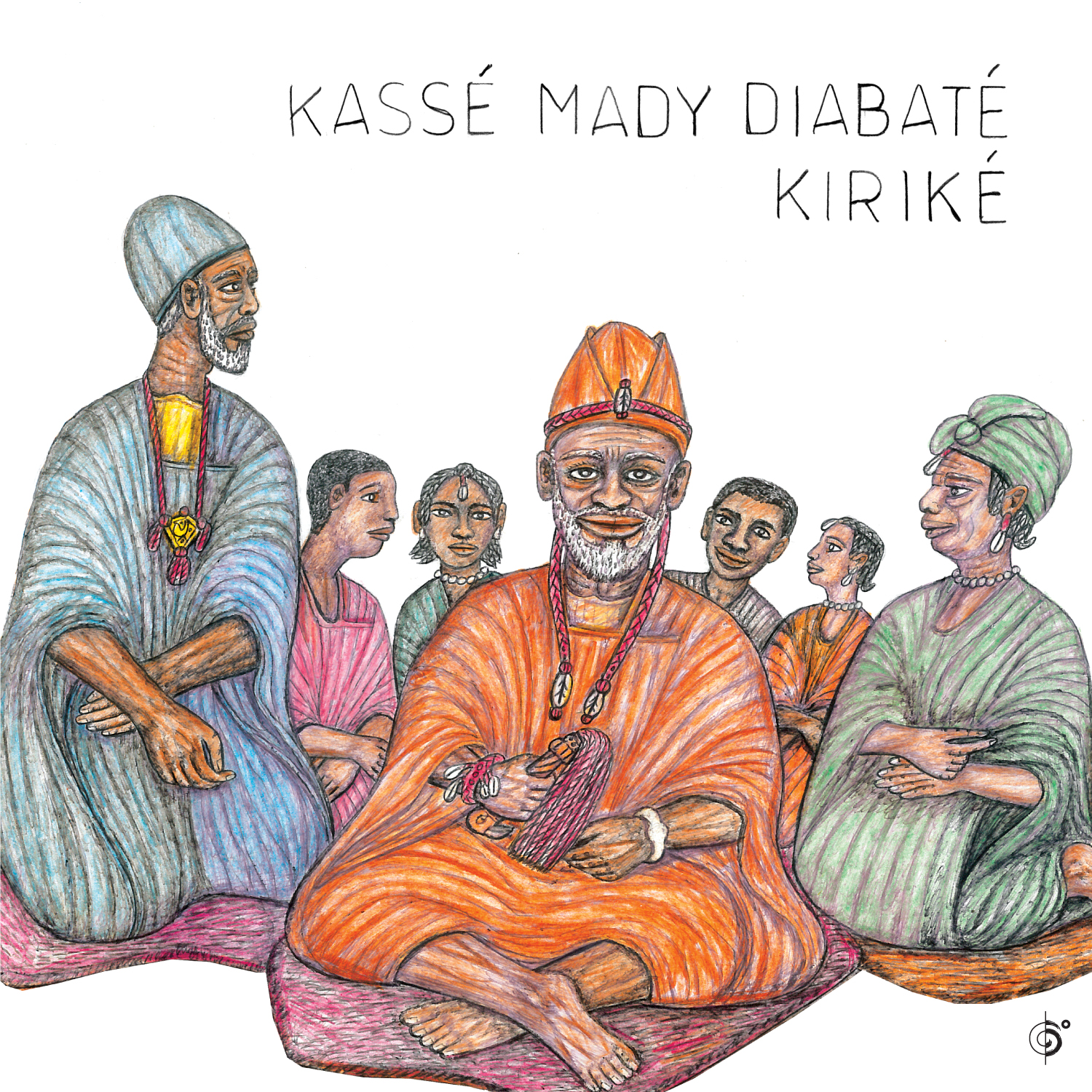

The new album Kiriké (out in the US on January 6, 2015 on Six Degrees Records) has provided a platform forKassé Mady to celebrate his position as one of Mali’s greatest voices in distinguished company. The album is the third in a series born out of the friendship between the young Malian kora maestro Ballaké Sissoko and the iconoclastic French cellist Vincent Segal. Already this friendship has resulted in two beautiful albums, Chamber Music (2009) and its follow-up At Peace (2012), both released on Six Degrees Records in the US. Kirike, like the other two albums in the series, exemplifies a more intimate musical current that has been emerging in Bamako, one that’s closer to the acoustic sound of tradition.

Having long been admirers of Kassé Mady, Ballaké and Vincent dreamt of assembling a royal ‘cast’ around him and making an album worthy of his extraordinary voice. So it was that three virtuoso soloists came together, childhood friends, one-time members of the National Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, and scions of Mali’s great griot dynasties.Ballaké Sissoko is the son of Djelimady Sissoko, the musical giant who recorded the album Ancient Strings, a cornerstone of modern kora music. Balafon player Lansiné Kouyaté is the son of Siramori Diabaté. (and so related to Kassé Mady). And ngoni player Makan Tounkara, aka ‘Badié’, grew up in the heart of the Instrumental Ensemble, his father being one of its directors.

The centerpiece is Kassé Mady’s voice. He sings in Bambara, the dominant language of southern Mali, and in doing so ‘the man with the voice of velvet’ reveals an altogether different personality: an old man of the soil grumbling at the margins of his field in a language infinitely rootsier and more flavorsome than the grand Malinké of the classic griot praise-songs. A fifty-year long career hasn’t blunted his high-notes, but rather added richness to the astonishing gentleness of his baritone, making his voice better suited to this ‘chamber music’ than to the brilliant sheen of fusionistic pop. It is a sound attuned to the modern ear, a consecration of one of Mali’s greatest voices.

Meanwhile the trio represent three major elements in Manding music: the kora music of Casamance, the balafon of the central zone and the more bitter sounding ngoni, so reminiscent of the northern deserts of Mali. And the music onKiriké keeps faith with that contemporary acoustic Bamako sound; the subtlety and simplicity of Vincent Segal’s approach allows the musicians to pour out their art with liberated ease, and show new facets of their talent. Thengoni, at once melodic and percussive, takes pole position, its stunning improvisations (‘Douba Diabira’) promising to dazzle amateurs of both Bach and jazz, of the gnaoua of Morocco and the trance music of Madagascar. Thebalafon and the kora conjure up novel moods, as in the liquid accompaniment they provide on the song ‘Sadjo’. And drawing all the sounds together is the stunning voice of Kassé Mady, dazzling with its range and power.

A griot to the core, Kassé Mady expresses himself almost entirely through his music, transcribing all of the nuances of the human soul into song. He is not especially at ease with the spoken word, and is known to all who come across him for his modest and peaceful character. But when he sings, his delivery embodies the power of his message it is this that cements his position as “the greatest singer in Mali”, as described by fellow countryman Salif Keita.

Albums