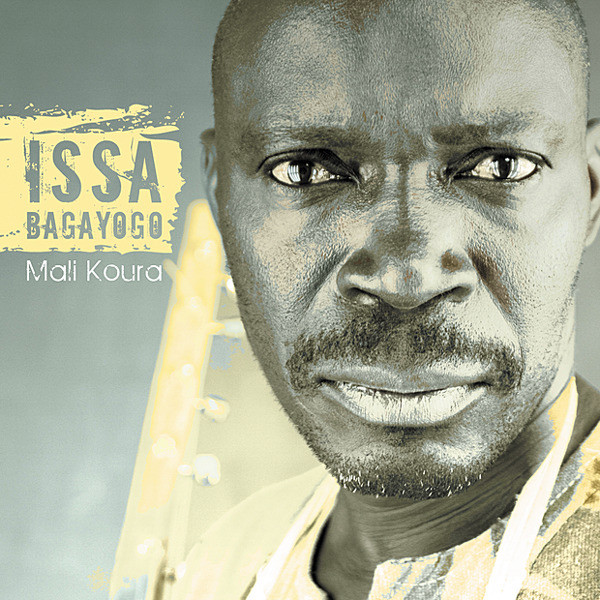

ISSA BAGAYOGO

Issa Bagayogo may seem like an unlikely candidate for international dancefloor success. His home country of Mali is one of the ten poorest nations in the world, and one in which economic and professional opportunities tend to be shaped by one’s caste and ethnic origins – and Issa’s heritage pointed him less in the direction of music than in those of blacksmithing and fishing. But at a young age he demonstrated a talent for playing the ngoni, a three-stringed lute that is popular throughout western Africa (under a variety of names) and may be the direct ancestor of the banjo. In Mali the ngoni is normally reserved for sacred contexts related to hunting, so youngsters who wanted to avoid controversy invented a six-string version for everyday use. This remains Issa’s primary instrument – another unlikely element in the story of his rapid ascent to worldwide fame.

In the mid-1990s, musical success looked even more remote. After making several recordings and failing to have a regional hit with any of them, Issa was making his living driving a bus while also descending into drug addiction. Eventually he lost his job and his wife, and moved back to the country to stay with his mother. But in the latter half of the decade he made the decision that would change his life and alter the face of the world music scene: he quit taking drugs, moved to Bamako (Mali’s capital city) and hit the studio again, this time working with a locally famous production team to create a highly personal sound that combined the acoustic traditions of his region with elements of rock, funk, dub and electronica.

Ten years and four albums later, Issa Bagayogo is a regular star attraction on stages around the continent, playing for huge and wildly enthusiastic audiences. His reception outside of Africa has been warm as well. Reviewing one of his pneumatic live shows, England’s Folk Roots magazine marveled at his energy, saying that he “may radically reshape West Africa’s groove… when Issa plays, only the dead stay still.” His second album, Timbuktu, hit the top of the CMJ New World chart, and Utne Reader called it “fine as Sahara sand,” while Billboard said it was time to “add this man’s name to the growing list of Mali’s emerging world-music luminaries.

The critical response to Tassoumakan, his third release, was even more enthusiastic. “His most appealing and ambitious record to date… a classic of modern Malian music,” raved Billboard, and the Village Voice characterized the album’s grooves as “the finest Afro-European rhythmic structures Mali can provide.” The All Music Guide concurred, pronouncing Tassoumakan “the perfect balance between roots music and modernity.”

The critical community must have been licking its chops in anticipation of Mali Koura, Issa’s latest release, which does not dissapoint. Issa’s sound has matured, tightened and ripened into a fully-realized Afro-European hybrid – no longer does it sound like a fusion of two separate cultures, but rather like the fully-evolved music of a brand new culture. On tracks like “Tcheni Tchemakan” there is a seamless blend of circular chord structure, call-and-response vocals (the lyrics sung in Wolof, of course), a relentlessly chugging, house-derived rhythm, and the subtlest touches of electronic texture filling in some of the spaces. Even the gently lurching and completely non-European rhythm of “Dibi” somehow absorbs and embraces the extended jazz chords and guitar runs that weave through the song like a silvery thread. On “Dunu Kan,” the groove is even jazzier, with a swinging horn section and a funky organ, while Issa’s vocals dance lightly and joyfully above them. There’s also a horn section on “N’Tana,” but here the horns are even denser, mirroring the sweet harmonies of the female backing vocalists; a woody-toned flute adds sturdy but elegant filigrees of sound while the beat churns tirelessly beneath. On this track, Issa’s vocal is declamatory but self-contained.

“Ahe Sira Bila” hints subtly at reggae, while the bassline incorporates popping funk elements and the vocals strike a calm, almost conversational tone. A marimba drops by to leave a string of pearlescent solo passages near the end. “Namadjidja” is darker and more regretful in tone, with a distantly plinking piano and quiet synthesizer moans over multilayered percussion. “Fimani” is custom-made for the dancefloor, with a bouncy four-on-the-floor beat, brightly tuneful harmony vocals, and horns that blossom unexpectedly out of nowhere before fading away as quickly as they emerged.

One significant reason that the music sounds different this time out is the dramatically different recording approach taken by Issa and his collaborators on this project. Producer Yves Wernert explains that normally, Issa proposes ten to fifteen songs to which the two of them then create arrangements in Wernert’s Bogolan studio. This time, however, “the strategy was completely different. For this new album, Issa recorded the songs freely on his own, all by himself outside of my house in Bamako – once in a while you can hear birds or mopeds going by. All of the Malian instruments were recorded more or less the same way, either outside the house or in my kitchen.”

Once he had the various instrumental tracks recorded, Wernert took them back to his home town of Nancy, France, where he got together with a number of musicians, most notably the fearsomely talented multi-instrumentalist Gael Le Billan; according to both Wernert and Issa, Le Billan brought a “tremendous effort” to the arranging and final production of these tracks, as well as contributing guitar, bass, keyboard, accordion and other instrumental parts. Interestingly, none of the additional tracks was recorded in a studio either – Wernert says that he “never once set foot in a studio during the making of this album.”

Almost as impressive as the unique recording approach is the roster of guest musicians who appear on Mali Koura. It includes flutist Ba Diallo (who plays regularly with the National Ensemble of Mali); the French guitarist Pascale Hubert (of Double Nelson); djembe player Adama Diarra (famed for his work with some of Mali’s greatest griots as well as jazz singer Dee Dee Bridgewater); and Issa’s longtime guitarist Mama Sissoko.

Take all of these elements together – a fully mature singer of international stature, a creative and musically sympathetic producer with resources and connections in both Mali and France; a constantly-expanding roster of enthusiastic sidemen anxious to participate in the transcontinental experiment; an out-of-the-box recording strategy – and the result is one of the warmest, most surprising and most exciting albums of African music in a decade.

Albums